Man, you should explode

Yourself to bits to start with

Jive to a savage drum beat

Smoke hash, smoke ganja

Chew opium, bite lalpari

Guzzle country booze—if too broke,

Down a pint of the cheapest dalda

Stay tipsy day and night, stay tight round the clock

Cuss at one and all; swear by his mom’s twat, his sister’s cunt

Abuse him, slap him in the cheek, and pummel him…

Man, you should keep handy a Rampuri knife

A dagger, an axe, a sword, an iron rod, a hockey stick, a bamboo

You should carry acid bulbs and such things on you

You should be ready to carve out anybody’s innards without batting an eyelid

Commit murders and kill the sleeping ones

Turn humans into slaves; whip their arses with a lash

Cook your beans on their bleeding backsides

Rob your next-door neighbours, bust banks

Fuck the mothers of moneylenders and the stinking rich

Cut the throat of your own kith and kin by conning them; poison them, jinx them

You should hump anyone’s mother or sister anywhere you can

Engage your dick with every missy you can find, call nobody too old to be screwed

Call nobody too young, nobody too green to shag, lay them one and all

Perform gang rapes on stage in the public

Make whorehouses grow: live on a pimp’s cut: cut the women’s noses, tits

Make them ride naked on a donkey through the streets to shame them

Man, one should dig up roads, yank off bridges

One should topple down streetlights

Smash up police stations and railway stations

One should hurl grenades; one should drop hydrogen bombs to raze

Literary societies, schools, colleges, hospitals, airports

One should open the manholes of sewers and throw into them

Plato, Einstein, Archimedes, Socrates,

Marx, Ashoka, Hitler, Camus, Sartre, Kafka,

Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Ezra Pound, Hopkins, Goethe,

Dostoevsky, Mayakovsky, Maxim Gorky,

Edison, Madison, Kalidasa, Tukaram, Vyasa, Shakespeare, Jnaneshvar,

And keep them rotting there with all their words

One should hang to death the descendents of Jesus, the Paighamber, the Buddha, and Vishnu

One should crumble up temples, churches, mosques, sculptures, museums

One should blow with cannonballs all priests

And inscribe epigraphs with cloth soaked in their blood

Man, one should tear off all the pages of all the sacred books in the world

And give them to people for wiping shit off their arses when done

Remove sticks from anybody’s fence and go in there to shit and piss, and muck it up

Menstruate there, cough out phlegm, sneeze out goo

Choose what offends one’s sense of odour to wind up the show

Raise hell all over the place from up to down and in between

Man, you should drink human blood, eat spit roast human flesh, melt human fat and drink it

Smash the bones of your critics’ shanks on hard stone blocks to get their marrow

Wage class wars, caste wars, communal wars, party wars, crusades, world wars

One should become totally savage, ferocious, and primitive

One should become devil-may-care and create anarchy

Launch a campaign for not growing food, kill people all and sundry by starving them to death

Kill oneself too, let disease thrive, make all trees leafless

Take care that no bird ever sings, man, one should plan to die groaning and screaming in pain

Let all this grow into a tumour to fill the universe, balloon up

And burst at a nameless time to shrink

After this all those who survive should stop robbing anyone or making others their slaves

After this they should stop calling one another names white or black, Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, or Shudra;

Stop creating political parties, stop building property, stop committing

The crime of not recognising one’s kin, not recognising one’s mother or sister

One should regard the sky as one’s grandpa, the earth as one’s grandma

And coddled by them everybody should bask in mutual love

Man, one should act so bright as to make the Sun and the Moon seem pale

One should share each morsel of food with everyone else, one should compose a hymn

To humanity itself, man, man should sing only the song of man.

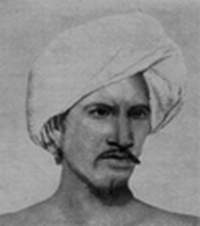

Found that Marathi poem by Namdeo Dhasal (from Golpitha, 1972), translated by Dilip Chitre, at the Almost Island site.